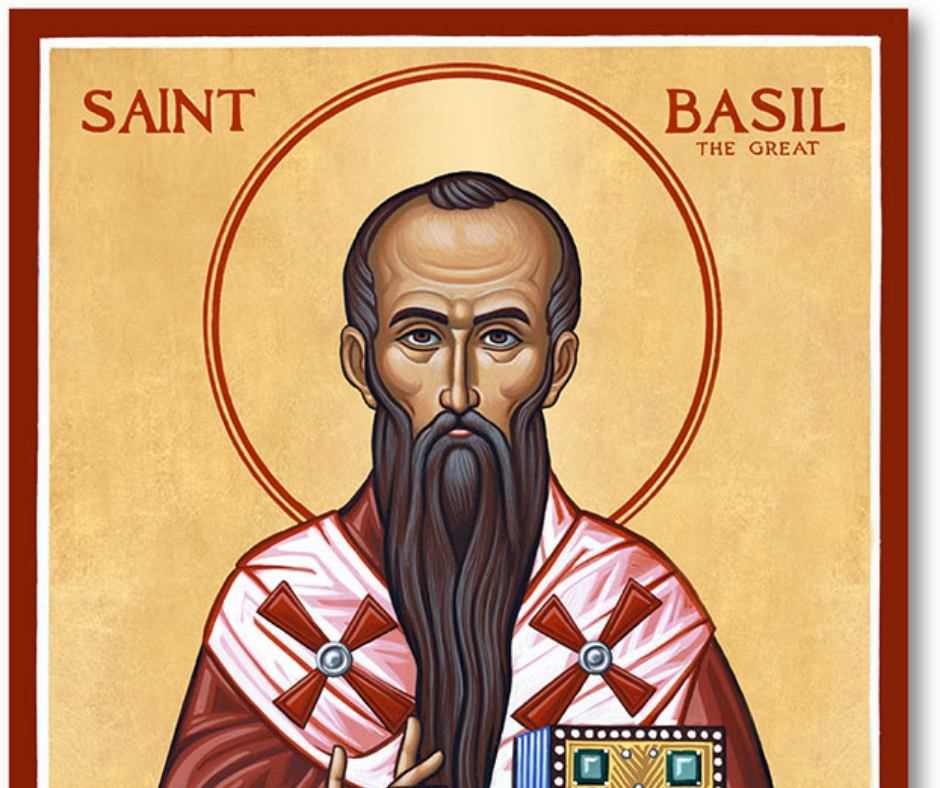

SAINT BASIL THE GREAT – Father of Eastern Monasticism c. 329–379: THE man in the judge’s seat insolently addressed without a title the Bishop summoned before him: “What is the meaning of this, you Basil, that you stand out against so great a prince and are self-willed when others yield?” Modestus, the powerful Pretorian Prefect, spoke for the Emperor Valens. The Emperor had sent him to Caesarea in Cappadocia to break down the opposition of St. Basil, its bishop, to the nearly all-pervasive Arian heresy. St. Basil had refused to communicate with the large group of Arian bishops who accompanied Modestus. Instead, when they assembled in his church, he spoke forthrightly, yet with such moderation that he incurred the wrath of the monks present who wanted to hear a burning condemnation. Now St. Basil pointed out to Modestus that though he was Prefect, still he was God’s creature, and that as such he was the same as any other person in Basil’s flock. In anger, Modestus rose from his seat and asked whether Basil did not fear his power.

Modestus pointed out that his power could mean for Basil confiscation of his goods, exile, torture and death. To this Basil replied: Think of some other threat. These have no influence upon me. He runs no risk of confiscation who has nothing to lose except these mean garments and a few books. Nor does he care about exile who is not circumscribed by place, who makes not a home where he now dwells, but everywhere a home whithersoever he be castor rather everywhere God’s home, whose pilgrim and wanderer he is. Nor can tortures harm a frame so frail as to break under the first blow. You could, but strike once, and death would be gained. It would but send me the sooner to Him for whom I live and labor, nay, am more dead rather than live, to whom I have long been journeying. Modestus objected that nobody had ever yet spoken that way to the Prefect. St. Basil said: “Perhaps Modestus never yet fell in with a bishop …”

Truly a Bishop: There is no doubt that Modestus could hardly meet a bishop more fully deserving the title than the man who was speaking. St. Basil was everything a bishop should be. He was a theologian of depth, an organizer, a good administrator, an eloquent speaker, a stylist in writing. He was an ascetic personal living and at the same time a keen social thinker and reformer. Many times he reminded the rich: “There would be neither rich nor poor if everyone, after taking from his wealthy enough for his personal needs, gave to others what they lacked.” St. Basil emphasized the Scriptures above all, yet he was the first of the Church Fathers to recommend the study of pagan classics. In the midst of the greatest difficulties—raging controversy outside and inside the Church—and personal sickness, he never neglected the details of promoting piety, developing the liturgy, establishing discipline, caring for the spiritual and also the temporal needs of all in his patriarchate. St. Basil has been a bishop for just nine years, from 370 A.D. Until his death on January 1, 379. In that short time he crowded activities that in their variety, scope and lasting value are astounding. When St. Basil was elected bishop, the great St. Athanasius himself wrote to express his pleasure. And well he might, for under St. Basil, the Diocese of Caesarea in Cappadocia (now northern Turkey, along the Black Sea) was to become the solid nucleus of the Catholic Faith in the East.

Defender of the Church against Arianism: After St. Athanasius, St. Basil is recognized as the greatest champion of the Church in the Eastern Roman Empire against Arianism and other fourth-century heresies. He is primarily responsible for the Eastern victory over Arianism, and is rightly known as St. Basil the Great. He laid the broad foundations for the Church’s second General Council and its denunciation of Arianism at Constantinople in 381, although he himself did not live to see this victory for the unity of the Catholic Church. Modestus had failed to shake St. Basil. He reported to Valens: “Emperor, we have been worsted by the bishop of this Church. He is superior to threats, too firm for arguments, too strong for persuasion. We must try one of the more ignoble. This man will never yield to menaces, or to anything but open force.” The Emperor sent two other emissaries, Count Terentius to try flattery, and Demosthenes the eunuch to threaten with the sword. Finally, the Emperor Valens himself came on Epiphany (January 6) of 372 and entered the church, accompanied by spear-bearers. The scene is a memorable one. The heretical ruler of the state had come to overawe a bishop. His entrance into the church caused no noticeable concern. The people continued to sing the psalms of the liturgy. Behind the altar, facing the people, stood the tall bishop—self-controlled, stern, his beard long, white and flowing, his face lean and pale.

He gave no sign at all of seeing the Emperor and his retinue. The fervor of bishop, priests and people, the perfect order and the power of this assembly united in the liturgical sacrifice, had a strong effect on Valens. When he came forward to make his offering, none of the priests made any motion to come to receive it. Waiting to see what St. Basil would do, Valens grew dizzy with emotion and would have fallen had not one of the priests stepped forward to support him. St. Basil took the Emperor’s gift and later met with him. When St. Basil spoke, it was as always, with the measured deliberation of one in deep thought, a manner others often tried to imitate. The Emperor left with no concessions from St. Basil; rather, he had signed over the income of his properties in Cappadocia for the poor. Later, however, Valens, under the influence of his Arian advisors, decided to send St. Basil into exile. Just before the order was to be carried out, the Emperor’s only son, Galates, age six, felt suddenly sick. Upon request, St. Basil went to pray for him, and the boy recovered. The promise to have the child baptized as a Catholic was not kept, and he died shortly after baptism by an Arian. Early Church historians tell us that when Valens tried still later to sign decrees banishing St. Basil, the pens split in his hands three times before he could make a mark on the paper.

From a Saintly Family: St. Basil was born about 329 A.D. In Cappadocia, the son of a family thoroughly Christian, refined and wealthy. His father, St. Basil the Elder, was a renowned teacher of rhetoric in Neo-Caesarea. He held estates in Pontus, Cappadocia and Lesser Armenia. His mother, Emelia (Emily), was a celebrated beauty who had been much sought after by many suitors. She gave birth to four sons and five daughters. Three of the sons became bishops and saints: St. Basil, St. Gregory of Nyssa, and St. Peter of Sebaste. The eldest daughter, Macrina, founded a convent and is also a Saint. She is known as St. Macrina the Younger, her paternal grandmother being St. Macrina the Elder. Basil’s mother is also honored as a Saint. St. Basil, his brother St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Basil’s friend St. Gregory Nazianzen is known as “The three Cappadocian Fathers.” As a young boy, St. Basil was put under the tutelage of his grandmother, Macrina. Later, his sister Macrina had a strong influence in directing him to the ascetical life. Few men have had the advantage of having mind and character formed by a grandmother, mother and older sister who would be canonized Saints, and by a father both holy and learned.

Basil studied at Constantinople, and then for nearly five years in Athens, the educational capital of the ancient world. Here his constant companion was St. Gregory Nazianzen. Here, too, he studied and associated with a student named Julian, who was later to become emperor and is now known in Church History as Julian the Apostate. St. Gregory Nazianzen says that when Basil was finished with his studies in Athens, he (Basil) had acquired “all the learning attainable by the nature of man.” St. Basil returned to Caesarea to teach rhetoric and plead the case of law. It was about this time that he was shocked by the sudden death of Naucratius, his younger brother. About this time, too, his sister Macrina died. He later journeyed through Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia, learning about the hermits, hermit communities and the nascent monasteries. On his return, he retired near Annesi, on the banks of the Iris River, to a life of solitude and penance. He gave away his possessions, wore sackcloth by night, a tunic and an outer garment by day, slept on the ground, ate sparingly of bread, vegetables and salt, and drank only water. Others came to join him. St. Basil maintained a similar strict mode of living later on as a priest and bishop. From this time forward, he was an ascetic, and he was to become known for great personal holiness.

Influential Writings: The writings of St. Basil was read by both the Christians and pagans of his own day. They were valued for their style as well as their content. St. Basil’s writings flowed directly from the task at hand. He wrote against Arianism and other heresies, composed sermons, made up rules of moral living for ordinary Christians and of ascetical living for monks, and wrote many letters. St. Basil’s doctrinal writings include On the Holy Spirit, Moralia and the Philocalia, a compilation of Origen’s writings which St. Basil and St. Gregory Nazianzen put together. His letters are edited in a series of 365, including some addressed to him by others. Of them it has been said that there is “probably no single source more important for understanding the complex period of the Arian controversy than the letters of Basil.” (The Month, March, 1958). His Letters Reveal His Personality: It may also be said that these letters provide much insight into the character of St. Basil, complex enough in itself, and yet simple because all the multiple outlets of his efforts and energies came from the single flame of intense and unswerving dedication to God.

The Letters of St. Basil have never rivalled the Confessions of St. Augustine in popularity, but they do rival the Confessions in uncovering the soul of a man aching over the sins and rebuffs of others and constantly accepting adversities as a punishment for his own sins. They show this man, who was so formidable to his enemies, often groping for strength in his own soul. They have flashes of wit and playfulness. They show that Basil, who could stand alone against all attacks, had such a sensitive spirit that he begged his friends for understanding. The letters indicate that St. Basil, whose ascetical way of living practically ignored the body, was often conscious of the body’s ills. He frequently mentions his weakness and sickness. The letters present a picture of one who made all sacrifices in order to put the love of God first, yet who retained deep affections and attachments for others. A letter written in the summer of 368, two years before he became a bishop, illustrates several of the above points. St. Basil is writing to his friend, Eusebius, Bishop of Samosata:… I pass over a succession of bodily ills, a tedious winter, vexatious affairs of business, all of which are known and have previously been explained to Your Excellency.

And now, as the result of my sins, I have been bereft of the only solace that I possessed, my mother. Pray does not deride me for bewailing my orphan hood at this time of life, but forgive me for not having the patience to endure separation from a soul whose like I do not behold those who are left behind. My ill-health has now returned again, and again, I lie on my bed, tossing about on the anchorage of my few remaining strengths and ready at almost every hour to accept the inevitable end of life. The churches exhibit a condition almost like that of my body: for no ground of good hope comes into view, and their affairs are constantly drifting toward the worse… Who would expect that the writer of this letter, bewailing the decline of the Church and sick unto death, would have the spirit, the energies and the knowledge to be the bulwark of the Catholic Church in the coming decade? Who would think that a man approaching 40 and yet calling himself an orphan, would be a hard drive of men and a leader of the finest courage?

A few years later, St. Basil, so tender-hearted in feeling toward his family and friends, was to exert the greatest pressure on his lifelong friend, St. Gregory of Nazianzus. He overrode Gregory’s protests and consecrated him bishop of the wretched town of Sasima. The word “bishop” may conjure up too exalted a picture. Actually, this act was like sending an outstanding orator, theologian and poet to a rough backwoods parish. St. Gregory never fully recovered from this blow to their friendship. Even St. Basil’s close friend and admirer, Eusebius, Bishop of Samosata, was shocked and wrote to St. Basil about it. And St. Basil wrote in reply that he too “could have wished his brother Gregory [of Nazianzus] to rule a church adequate to his nature. But this would have been the whole Church under the sun collected into one. Since, then, this is impossible, let him be a bishop who gives dignity to his See, and not one who gains his dignity from it. For it is the part of a truly great man not only to suffice for great things, but even by his own capacity to make little things great.” In contrast to these words, hard-polished in literary form and in sentiment, we may recall St. Basil’s playful words to Libanius, the great rhetorician: … I have written my letter while covered over with a blanket of snow. When you receive it and touch it with your hands, you will perceive how icy-cold it is in itself and how it characterizes the sender, who is kept inside and is unable to put his head out of the house. (1349).

Pride or Humility?: The strong and complex character of St. Basil is again well indicated by the fact that at one time he fled from a position of influence and a few years later cooperated in winning for himself the bishopric. He left Caesarea when there was a possibility of a schism developing because of his presence. He retired to his solitude and retreat on the Iris. He returned to Caesarea in 365 at the request of his friend, St. Gregory Nazianzen, who had asked him to return because of the new, insistent dangers of Arianism, which old Bishop Eusebius could not cope with. In 370, when Eusebius died, those who loved the cause of the Catholic Church knew that St. Basil was the man to succeed him, to save the Church in that area from the still strong surging Arianism. St. Basil had been practically the head of the diocese for the past five years. He was an able theologian, firmly in the direction, respected for his power, though certainly not loved by all. The wealth of the city wanted somebody less ascetical, somebody less direct in pointing out their social obligations. Some of the people wanted a bishop who would not always denounce their circus and amphitheater. Some said that Basil’s health was too poor. (In reply, the elder St. Gregory Nazianzen asked whether they wanted a bishop or a gladiator.) The suffragan bishops, especially disliked St. Basil. Nevertheless, largely through the efforts of the elder Gregory Nazianzen, those who had the power of election were led to choose Basil. St. Basil was willing to be bishop. Had he not been so and had he not cooperated with those who helped him, the fact could never have been accomplished. Not three bishops could be found among the 50 suffragan bishops (chor-episcopi) of Cappadocia to consecrate Basil.

The aged Gregory, sick in bed, had himself carried to Caesarea to take part in the consecration. But St. Basil, often accused of pride by his enemies, and at times even by his friends (St. Jerome being among the accusers), and also of imperiousness, did not want the bishopric for any reason of vanity. He simply knew that he was needed. In this and in other instances of his life, he does not fit the pat picture of humility, i.e., always backing away from the influence and honor. Yet perhaps he was the manliest humility of braving charges of pride, and the more complete detachment from self for refusing to hide in the safe compartment of false modesty. Certainly the bishopric of Caesarea, with its 400,000 inhabitants and its commanding influence over a large part of Asia Minor, was no bed of roses. Not only was there the attack of Arianism from the outside; there was the more heart-rending opposition from within. Of this latter condition St. Basil said in a sermon: The bees fly in swarms, and do not begrudge each other the flowers. It is not so with us. We are not in unity. More eager about his own wrath than his own salvation, each aims his sting against his neighbor. St. Basil was nothing if not plain-spoken. Even his uncle, Gregory, also a Cappadocian bishop, was for a time against him. The disaffected bishops refused to come to Caesarea. But when a false report went out that Basil was dead, they all came into town. He used this occasion to address them, urging peace for the love of the Church.

His Influence on the Liturgy: St. Basil has had a lasting influence on the liturgy. He noticed the weariness of the people at extremely long services and shortened the public prayers. At the same time, he introduced the prayers of Prime and Compline into the monastic office. His providing for eight periods of prayer in his monasteries has helped to determine this number for the hours or periods of prayer, of the daily Divine Office, prayed for centuries by priests and many religious. The liturgy of the Orthodox churches, even in our time, according to their tradition, is largely that which St. Basil introduced and/or revised at Caesarea. Parts of this liturgy are also in use in present-day Byzantine liturgies. “Father of Eastern Monasticism”: St. Basil’s interest in monasticism was wider than merely a regard for the ascetical life itself. He considered that well-directed monks could be a chief weapon in defending the Church from heresies. The trend of his regulations reflects this general purpose. St. Basil has had a great and lasting effect in shaping monastic life and spirit. He did not find an order in the strict sense, but he did find many monasteries. For this reason and for his strong formative influence he is rightly called the “Father of Eastern Monasticism.” Moreover, since later founders in the West, such as St. Benedict, we’re able to make use of his writings (in the Latin translation of Rufinus), St. Basil’s influence has extended to the whole Church. The Rules of St. Basil is known as the Long Rules or the Detailed Rules, 55 in number, and the Short Rules, of which there are 313. The Long Rules explain the principles and the Short Rules apply them to the daily life of a monk. Earlier steps in the development of monastic life are represented by St. Antony of the Desert in northern Egypt, who gave direction to other hermits who gathered around him, and by St. Pachomius in southern Egypt, whose monks wore a habit and took vows, but were free to arrange much of their daily schedule according to their own wishes.

St. Basil introduced the spirit of the common life, in which the day was ordered for all. Thus the element of obedience to a superior became much stronger. Moreover, in Basilian monasteries moderation replaced much of the primitive exaggeration and even rivalry in bodily penance that had sometimes existed. However, St. Basil’s standards of moderation still seem very severe compared to our modern practice. St. Basil also gave a stronger emphasis to work than to bodily penance. At work he saw a discipline for body and the will and the means of fulfilling the command of loving one’s neighbor. His monks were to help strangers, put up travelers, care for orphans, educate children. They were to learn trades like carpentry and architecture; they were to maintain gardens and farms. St. Basil’s fusing of work and prayer gave a direction to monastic practice which to a large extent it has retained. His monks were not to flee from all contact with mankind, but were to raise themselves to spiritual perfection largely by helping others. The exercise of the love of others was to lead to a purer love of God. Yet St. Basil insisted on the primacy of prayer and recollection in order to do this well. He believed, too, in the value of external practices: “For the soul is influenced by outward observances and is shaped and fashioned according to its actions.” St. Basil illustrates: One regular hour is to be assigned for meals, so that of the twenty-four hours of the day and night, just this one is devoted to the body, the remaining hours to be wholly occupied by the ascetic in the activities of the mind. Sleep should be light and easily broken, a natural consequence of the meagerness of the diet, and it should be deliberately interrupted meditations on lofty subjects. The midnight Office may owe something to St. Basil, for he says, “What dawn is to others, this, midnight, is the men who practice piety.”

The Strength of Weakness: It has been said that the later years of St. Basil’s life has been just one long sickness. Cardinal Newman says of St. Basil that “from his multiplied trials he may be called the Jeremiah or Job of the fourth century… He had a very sickly constitution, to which he added the rigor of an ascetic life. He was surrounded by jealousies and dissensions at home; he was accused of heterodoxy in the world; he was insulted and roughly treated by great men; and he labored, apparently without fruit, in the endeavor to restore unity and stability of the Catholic Church.” Cardinal Newman does not explicitly say so here, but even Pope St. Damasus suspected St. Basil of heresy. Basil’s efforts to have St. Damasus comes to the East met with no success, and while Basil’s ensuing bitterness indicated his intense dedication to Church unity, it showed to the personal pain of being misunderstood. St. Basil had been a sickly child to start with, and as mentioned above, much of his later life was spent in illness. He speaks often in his letters having been laid up for some time. One of his longstanding ailments was liver trouble. Once when St. Basil stood before the tribunal of the sub-prefect of Pontus, the magistrate threatened to tear out his liver. He replied, “Do so, it gives me much trouble where it is.”

He often mentions that the blows to his spirit from misunderstanding and calumny brought on relapses. My heart was constricted, my tongue was unnerved, my hand grew numb, and I experienced the suffering of an ignoble soul… I was almost driven to misanthropy. Every line of conduct I considered a matter of suspicion, and I believed that the virtue of charity did not exist in human nature, but that it was a specious word which gave some glory to those using it… But St. Basil did not become embittered by his constant sickness. Instead, he built on the outskirts of Caesarea a large hospital, together with houses for workers, a shelter for travelers, a church and a home for clergy. In one section of the hospital, St. Basil himself received and embraced lepers, just as a decade before he had himself served meals in the soup kitchen which he had organized during a year of famine. Other buildings were situated nearby, so that the area came to be called “The New City.” St. Basil also established many other hospitals in his diocese.

St. Basil is truly the bishop par excellence. He devoted himself to everything that pertained to Church life. His supreme interest was the unity of the whole Church, and for this he wrote letters to St. Athanasius, the bishops of the West and to Pope St. Damasus. At the same time, the bodily needs of the poorest man in the city received his energetic attention, and he could take time to write to a tax assessor or a poor widow. St. Basil’s last act before death was to ordain. His last words were, “Into Thy hands I commend my spirit.” At St. Basil’s funeral, several people were crushed to death trying to get close to his bier. Today his name will cling only to one of the hills of ancient Caesarea (modern Kayseri). The New City is gone. But both the work and the name of St. Basil endures in the Church. He touches our lives at many points. His feast day (June 14 in the 1962 calendar) is now observed in the Roman Rite on January 2, along with that of St. Gregory Nazianzen. The Eastern Rites celebrate St. Basil’s feast on January 1, the anniversary of his death. Deservedly has he retained the title first given by his own contemporaries: Basil the Great.