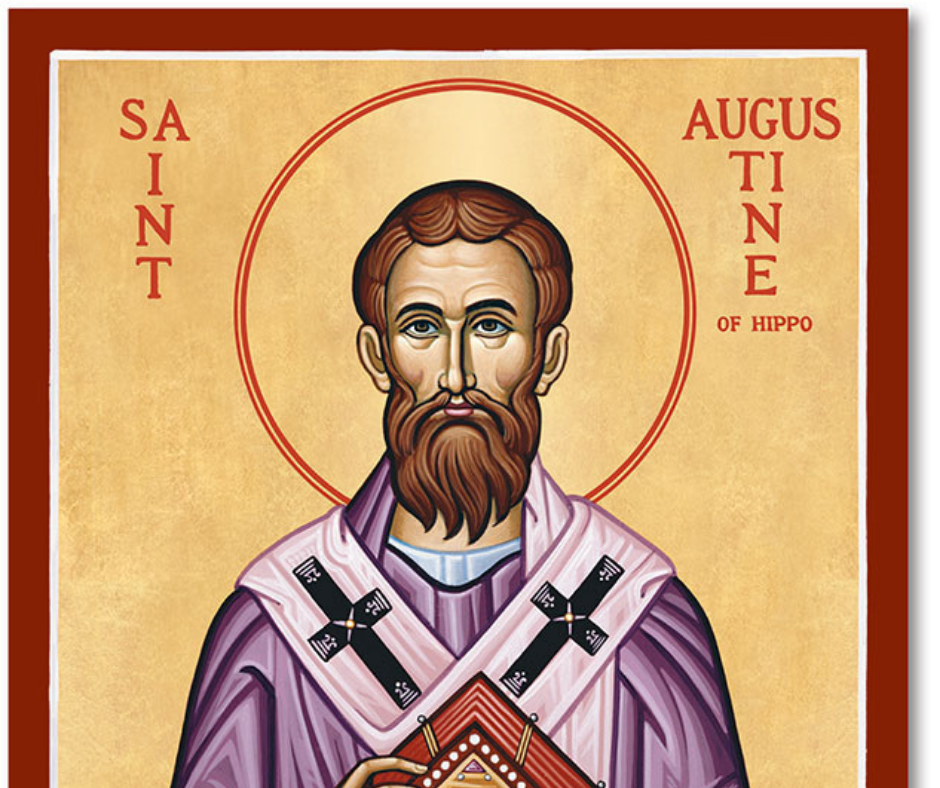

Saint Augustine, Doctor of Grace, Doctor of Doctors(354–430): THE world’s most famous autobiography begins, not by focusing on the writer, but rather on the Divine Author of all things. “Great art Thou, O Lord, and greatly to be praised… Thou hast made us for Thyself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.” It was 10 years after his conversion, in about 397 A.D., that St. Augustine wrote his Confessions. He was in his early forties and had been a priest for eight years. Just the year before he had succeeded Valerius as Bishop of Hippo, an ancient city on the north coast of Africa, whose ruins now lie about a mile and a quarter southwest of modern Bona in Algeria.

The new bishop of Hippo was gaining renown for learning, for oratorical prowess, and for holiness. He was a man who loved the truth intensely, whose whole life would be spent in seeking out the secrets of nature and Divine Revelation. He wrote the Confessions because he loved the truth; he wanted men to know the kind of man he had been and how much he owed to God’s mercy. Later, he said in a letter about his Confessions: “See what I was by myself and by myself. I had destroyed myself, but He who made me remade me.” Revelations of personal life are often made to men in order to amuse, interest or shock them. St. Augustine confesses to God.

In the very style of his writing, he tells the story of God, and while he relates the facts of the past, he keeps breaking in with the overflowing thanksgivings and petitions of the present. For a thousand years, or until the publication of the Imitation of Christ, St. Augustine’s Confessions were the most common manual of the spiritual life. In his own lifetime and ever since, his Confessions have had more readers than any of his other works. New translations are still appear in the major languages of the world. New generations of Christians are learning from St. Augustine’s own story how to quiet the restless heart of man and bring it closer to God, its real happiness. The long procession of readers still find re-echoing in their wayward hearts St. Augustine’s own touching and plaintive words: Too late have I loved Thee, O Beauty ever ancient, ever new. Too late have I loved Thee. For behold, Thou wert within, and I without, and there did I seek Thee. I, unlovely, rushed heedlessly among the things of beauty which Thou madest. (Bk. 10, 27, 38).

St. Augustine was born at Tagaste, in Northern Africa—now Souk-Ahras, Algeria—50 miles south of Hippo, on November 13, 354. Other children that we know of in the family were a brother, Navigius, and an unnamed sister. She became an abbess of a convent in Hippo. It was shortly after her death that Augustine wrote a letter to her successor, giving advice when questions arose about the government of the convent. This letter is the chief basis of “The Rule of St. Augustine,” on account of which St. Augustine ranks as one of the four great founders of religious orders. Augustine’s father, Patricius, was a man of quite modest means, ambitious for Augustine’s worldly success, but not quite able to pay for a complete education. Patricius was a pagan until shortly before his death.

St. Augustine has painted an enduring picture of his mother, St. Monica, silent under the abuse of a violent-tempered husband, devoted to the service of God and neighbor, never repeating scandals but rather helping to reconcile enemies. St. Augustine’s appreciation of this virtue of his mother grew with the years: I should have thought this a small virtue if I had not learned by sad experience the endless troubles which, when the horrid pestilence of sins is flowing far and wide, are caused by the repetition of the words of angry enemies and by their exaggeration. It is a man’s duty to do his best to alleviate human enmities by kindly speech, not to excite and aggravate them by the repetition of slanders.

St. Augustine’s Fall: Because of lack of money, St. Augustine had to leave school during his sixteenth year. Idleness and degenerate companions, plus the strong passions of his youth, combined to lead him into sins of impurity. He resumed school the next year at Carthage, a city of perhaps half a million, which offered fine literary oppor-tunities—but in a degraded moral atmosphere. Augustine continued to frequent the theater, which in those days was grossly immoral and allied to the worship of pagan gods and geared to satisfy human passions. The chief shame he felt was not joining in with the worst exploits of rowdy gangs. At the age of 17 he entered into a union with a girl with whom he would live for 14 years. Though the union was not a marriage, the parties were faithful to each other, and for Augustine it was a stabilizing influence and most likely a lesser evil than his former practices. One child was born to the couple, the boy Adeodatus (“given by God”), who was extremely bright and highly spiritual, giving high promise until his death in his late teens.

There is something elusively great about this unknown woman who proved an adequate companion to share the richness of Augustine’s active and probing mind. There is something poignant about the way she marched off silently at his command, leaving her cherished son and leaving Milan to go back to Africa to spend her final years in chastity until she was laid in an unremembered grave. Into the darkness, she glides, a silent shame And a veiled memory without a name. And the world knows not what words she prayed, With what she wail before the altar wept, What tale she said, what penitence she made, What measure of beating heart was kept…

Augustine earned his living by teaching. First, he taught grammar in his native town of Tagaste, then rhetoric at Carthage, Rome and Milan, spending the longest time, a period of 10 years, at Carthage. He left this city because of the undisciplined conduct of some of the students, especially the accepted practice of bands of outside students coming in and breaking up classes. He left Rome because too many of the students had the unfortunate habit of failing to pay their tuition. Still, he was an esteemed and very successful teacher. At Milan he was beginning to win political favor. He could soon have hoped for some position in the government.

For nine years, from the age of 19 until age 28, Augustine, to the great sorrow of his mother St. Monica, belonged to the sect of the Manicheans. This heretical group, named after the Persian Manes, had a threefold appeal to Augustine. Their teaching of a principle of evil, helped to explain to him, and to excuse, his sins. Moreover, they claimed to have scientific explanations unlocking the mysteries of nature. The Manicheans also pleased Augustine’s intellectual pride by belittling faith and authority. In substance they argued: “The Church asks you to believe what cannot be supported by reason. We do not force your mind, nor threaten you with future punishments.

We merely invite you to accept the truths which we first explain.” The ever-inquiring mind of Augustine found questions they could not answer, but he was put off with the promise that when he heard their great bishop, Faustus, all would be clear. When Augustine finally heard Faustus, he was charmed by his rhetoric, but very disappointed by his knowledge and logic. Thereafter, he temporarily became a skeptic. These intellectual groupings, along with Augustine’s interest for some time in astrology, are very revealing. They show us that even truly great minds require development and, in matters of religion, the guiding hand of active faith.

His Conversion: St. Monica had earlier approached a Catholic bishop, who had himself once been a Manichean, and had asked him to talk to Augustine. He declined, saying it would be of no use. But noting her earnestness and tears he added: “Go and continue to live so; it cannot be that the son of those tears will perish.” The tears and prayers of St. Monica finally did win out. St. Ambrose’s sermons, the story of the conversion of Victorinus, a great pagan orator, the reading of St. Paul’s epistles, all had a disposing effect on Augustine. But one day a fellow countryman, Pontitian, came to Milan and recounted how some of his associate military officers had vowed a life of chastity after reading St. Athanasius’s Life of St. Antony of the Desert. St. Augustine was highly affected.

Even after sending off his faithful mistress, he had weakly taken another. He had continued his prayer for many years (which was at least an honest one): “Lord, make me pure, but not yet.” Now he asked his lifelong friend, Alypius: “What is this? The unlearned rise and take Heaven by force, and we, with our learning, but without heart, see we are rolling ourselves in flesh and blood.” It was then that he rushed out into the garden, flung himself under a fig tree and cried out: “How long, O Lord, how long? Remember not my former sins! Tomorrow and tomorrow—why not now?” About this time, he heard a child’s voice sing, singing over and over something that sounded like: Tolle, lege; tolle, lege. (“Take and read; take and read.”) Augustine, remembering how a random opening of the Bible had guided St. Antony, took this for a sign that he should open a book and read the first thing he found.

He took up the copy of St. Paul is lying by Alypius in the garden and opened it to Romans 13:13–14, where he read: “… not in rioting and drunkenness, not in chambering and impurities… but put ye on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh in its concupiscences.” This was in the summer of 386. At Easter of 387 he was baptized by St. Ambrose, together with Adeodatus and Alypius. It seemed that St. Monica’s life-work was over; perhaps she had offered her life for the conversion of her son. For she suddenly took sick and died at Ostia, a seaport town a few miles south of Rome. St. Monica was 56, St. Augustine 33. Monica had always wanted to be buried beside her husband in her native Africa. But when her tearful sons asked her, during her last illness, where she wished her last resting place to be, she gave them the following reply, so full of faith in the Mass: “My sons, bury this body where you will; do not trouble yourselves about it. I ask of you only this—remember me whenever you come to the altar of God.”

Bishop of Hippo: St. Augustine returned to Africa and lived a quiet, monastic-type life at Tagaste. When he did travel, he purposely avoided towns in which there was a vacant bishopric, fearing to be chosen a bishop, as had Ambrose and many others. He wanted nothing but a monk’s life. Then one day he went to Hippo, which had a good, healthy bishop in the person of Valerius. Augustine felt perfectly safe in going into the church and standing with the congregation. But Valerius, a Greek, had been anxious for some time to secure an outstanding priest who could preach in better Latin than himself. With Augustine present, he spoke fervently on the need for a priest to help him. The congregation took up the cue and began to clamor for the ordination of the unsuspecting Augustine. His tears and entreaties could not change their minds; therefore, against his own inclination, but seeing in all this the will of God, he allowed himself to be ordained.

Five years later he was made a bishop, and in the following year, 396, he succeeded Valerius as bishop of Hippo. For 34 years he governed this diocese, giving lavishly of his talent and energy for the spiritual and temporal needs of the people, who were mostly unlearned and simple. At the same time, he wrote constantly to refute the false teachings of the day; he went to the councils of bishops in Africa; and he traveled to neighboring Sees to preach for special occasions. He soon emerged as the leading figure of Christianity in Africa and the most outstanding personality in the whole Church. In August of 430, St. Augustine took sick. Outside the city walls, the Vandals, under Genseric, were in the third month of a siege. Inside, at Augustine’s request, his friends hung on the walls of his room copies of the seven penitential psalms written in large letters. He read them over and over. On August 28, at the age of 76, St. Augustine’s soul went forth to rest in God.

His body was buried in Hippo, later moved to Pavia in Italy, and in our present day returned to Bona, in North Africa. After St. Augustine there has been no other bishop of Hippo. The flourishing Church of North Africa, which he had spent his life working for and building up was reduced to a mere trace. At St. Augustine’s death, there were about 500 bishops in the African province. Twenty years later there were less than 20. His immediate work was reduced to ashes, like his body, but his enduring work in the Church, like his immortal soul, has continued through the centuries. St. Augustine was the greatest contributor of new ideas in the history of the Catholic Church. Excepting St. Paul, he is undoubtedly the Church’s greatest convert. In the Latin Rite, only two conversions are observed, that of St. Paul, on January 25, and of St. Augustine, on May 5 (observed in the Augustinian Order).

Defender of Catholic Truth and Unity: St. Augustine’s love for truth brought him into contention with the proponents of error. We can divide his long career as priest and bishop, covering about 40 years, into three parts, which correspond to the errors he wrote and spoke against. Counting round numbers, the first 10 years were employed in fighting against the Manicheans, to which sect he had formerly belonged. The next 10 years were occupied with the Donatist schismatics in Africa. During most of the final two decades of his life, St. Augustine combatted the Pelagians. The Donatists were very numerous in Africa. They had broken away from the Catholic Church and claimed that they alone were the True Church. In arguing with and writing against them, St. Augustine developed many proofs for the unity, universality and authority of the Catholic Church. He often pointed out to the Donatists that they existed only in Africa, and that all false sects were found chiefly in one geographical location. Therefore, they could not be truer, universal Church. Only one Church was spread throughout all the nations of the world.

The Church is spread throughout the whole world: all nations have the Church. Let no one deceive you; it is true, it is the Catholic Church. Christ, we have not seen, but we have her; let us believe as regards His. The Apostles, on the contrary, saw Him, but they believed as regards her. (S. 238). In another sermon, St. Augustine says: “Indeed, it was precisely in Peter himself that He [the Lord] laid emphasis on unity. There were many disciples, and only to one there is said, ‘Feed my sheep…’” In a great meeting at Carthage in 412 A.D., with 286 Catholic bishops and 279 Donatist bishops present, St. Augustine played the leading role in refuting the schismatic.

St. Augustine continued to uphold in unmistakable terms the unity of the Church: We must hold fast to the Christian religion and communion with that Church which is Catholic, and is called Catholic, not only by its own members but also from all its enemies. For whether they will or not, even heretics and schismatics, when talking not among themselves but with outsiders, call the Catholic Church nothing else but the Catholic Church. For otherwise they would not be understood unless they distinguished the Church by that name which she bears throughout the whole world. (Synthesis, p. 249; from De vera relig. 7,12).

St. Augustine sums up very neatly the way in which nuggets of truth are mined from Scripture: “For many things lay hid in the Scriptures, and when the heretics had been cut off, they troubled the Church of God with questions; those things were then opened up which lay hid, and the will of God was understood.” (In Ps. 54, 22). St. Augustine recognizes this value of controversy, but bewails the loss of the true fold. “Nevertheless, the Catholic mother herself, the Shepherd Himself in her, is everywhere seeking those who are straying and is strengthening the weak, healing the sick, binding up the broken—some of these sects, some from those, which mutually do not know one another.”

“Doctor of Grace”: St. Augustine won his title of “Doctor of Grace” especially in combatting the Pelagians. With them, he had foes of higher acumen than ever before, and he himself refers to their “great and subtle minds.” In explaining Psalm 124, he says: “For you are not to suppose, brethren, that heresies could be produced through any little souls. None save great men have been the authors of heresies.” In God’s dealing with men, there is scarcely anything harder to explain than the working together of grace and free will. In fighting the Pelagians, who overstated the role of free will, St. Augustine made a very strong case for grace and man’s complete dependence upon it. In doing this he grappled with the problems connected with man’s nature—Original Sin, infant Baptism and predestination.

He is the great pioneer in this most difficult field, although the common teaching of the Church on grace is more moderate than his system. His severe opinion on the punishment of unbaptized infants, for example, is not generally held. St. Augustine was driven by very powerful foes and perhaps attempted to apply logic beyond its possibilities, as this position was certainly beyond the feelings of his own heart. He has led the Church in most points he held, but the Church had not followed him in every way. It was in reference to the condemnation of Pelagianism by Pope Zosimus in 418 that the famed expression arose: Roma locuta est, causa finita est—(“Rome has spoken, the case is closed”). St. Augustine did not say these words in just that way, but he did express the same sense. He said in a sermon (131): There have already been sent to the Apostolic See two delegations concerning this case, and the answers have come back. The case is finished, and would that the error were also finished.

Interested in Every Person: One of the keys to understanding St. Augustine is to realize his concern for each person. It was his interest in one individual that brought him to Hippo from Tagaste and started the sequence of events that so changed his life, that turned him from the seclusion of penance and study to the active life of priest and bishop. He went to Hippo in response to the request of a man who was considering a life of poverty and renunciation. This man wanted to hear from Augustine’s own lips the reasons for doing this. Why should this “agent in God’s affairs” not have been expected to go to Augustine? It was certainly the mark of a magnanimous soul, a person interested in each individual, that Augustine left his prayers and studies and traveled 50 miles to help this man.

St. Augustine thought so much of each individual’s importance that he said God had some verse or a few verses in Scripture especially for particular people. (Conf. 12, 31). The Holy Spirit intended a primary meaning, but He also intended the special and varied aspects of truth that many individuals would see in certain passages. This belief of St. Augustine also gives an insight into his overwhelming sense of Divine Providence. St. Augustine’s books, too, sprang up as answers to the immediate needs of the Church in his time. He was a great speculative philosopher and theologian, but his aims were practical and close at hand. His biographer, Bishop Posidius, when trying to list all of St. Augustine’s works, simply classifies them according to the opponents he had encountered. (The Life by Posidius in Early Christian Biographies, ed. Roy Deferrari, 1952, in the series Fathers of the Church).

It was at the request of his friend Marcellinus that St. Augustine started his monumental City of God. It began as a fairly simple and short answer to the charge of the pagans that Christianity was responsible for the fall of Rome. St. Augustine continued to write it over the years 413–426 until it ended as a massive theology of history and the best early Christian apologia for the truth of the Catholic Church. The “City of God” is the Catholic Church. The plans of God will be worked out in history as the organized forces of good in this City gradually overcome the organized forces of the temporal order that war against the will of God.

So it is that the two cities have been made by two loves: the earthly city of love of self to the exclusion of God, the heavenly by the love of God to the exclusion of self. The one boasts in itself, the other in the Lord. The one seeks glory from men, the other finds its greatest glory in God’s witness to its conscience. The one holds its head high in its own glory, the other calls its God “my glory who raises high my head”… Thus the one has men wise by human standards, who have made the good things of body, of mind, or of both, their ultimate aim; even those of them who have been able to come to some knowledge of God did not honor Him as God, or give thanks; but they faded away in their own thoughts, and their foolish heart was darkened, calling themselves wise; that is, being eaten with pride and preening themselves on their wisdom, “they became foolish and changed the glory of the incorruptible God into the likeness of the image of corruptible man, and of birds and beasts, and creeping things,” in that they either led or followed the populace in the worship of such idols; “and they worshipped and served the creature instead of the Creator,” who is blessed forever. (City of God, 14, 28).

His Sermons: It has been remarked many times that there is a great difference between St. Augustine’s sermons and his more formally written works. The sermons are in a much simpler style, adapted to the congregation at Hippo. He did not try to dazzle, but to instruct and to make himself plain. For this reason his more than 500 extant sermons still have reader appeal today. St. Augustine also showed his awareness of individual needs when he delivered his sermons. He was alive to the reactions of his listeners. He made remarks as he went along, such as, “I see that you do not agree with me.” “Perhaps some of you are saying in your hearts, ‘Oh, if only he would let us go.’” At other times he said more optimistically, “I see that you approve.” St. Augustine wrote so voluminously that Posidius, after counting up 1,030 of his works, expresses his doubt that any man could ever read all that he wrote. Yet St. Augustine did repeat himself. And he was sensitive to unspoken criticism when he repeated himself.

Many of you know what I am going to say. But those who do know must put up with the delay; for when two are walking on the road and one goes fast while the other is slower, it is up to the fast walker to secure that they both keep together; for he can wait for the slower man. The person, then, who knows what I am going to say is like the fast walker and must wait for his slower companion. St. Augustine knew that some of his hearers needed the repetition. Perhaps, too, he at times felt the burden of always coming up with new material. Once he explained: “It should not be necessary for me always to say something new. The real point is that we have to be new.”

In later years he complained that wherever he went, he was always expected to deliver the sermon. After many long years, he would be more content to listen and allow someone else the honor and the burden. In those days, naturally, there were no microphones, and the physical labor involved in making oneself heard was harder than it is today. St. Augustine’s basilica in Hippo, when excavated, was found to have been 60 x 129 feet in the central part, with a rounded apse 22 x 25 feet. Therefore, the preacher of sermons in this church would have had to speak quite loudly in order to be heard by all, and such public speaking demands a great deal of energy.

It is interesting to note that St. Augustine, who except for Origen was the most prolific writer, among the Church Fathers, disliked the physical labor of using the pen. Also, at an early age, he conceived a decided dislike for Greek. Though he later renewed his study of this language, he never acquired a mastery of it. St. Augustine’s health was not robust. He did not make long trips, and after becoming bishop, he attended only councils held in Africa. In sermons he at times mentioned that he was tired. Sometimes the sermon would be surprisingly short, although at other times it would be extremely long. Changes in temperature often affected him. “The heat is so great that I cannot say much.” More often he was affected by the cold. He found it necessary to wear shoes, though he wanted to do without foot-gear for the love of the poverty and simplicity mentioned in the Gospel.

When St. Augustine was a bishop, his table was very simple. Ordinarily he ate no meat, though he did drink wine. Also, a certain number of cups of wine were allowed to members of his household. Anyone who swore was penalized by losing one cup that day. On the table were inscribed the words: “Whoever likes to chew on the life of one who is absent, let him know that he is not welcome at this table.” St. Augustine placed charity above politeness, and one day he pointed out this inscription to a group of offending bishops dining with him. In trying cases of law, which as a bishop, he faithfully did in the mornings, he preferred to pass judgment on strangers rather than on friends. He remembered the saying, “When you judge strangers, you might win one friend, the one who receives the favorable judgment. But when you judge friends, you lose one.”

Once St. Augustine had chosen chastity as a way of life, he remained firm. He was also very circumspect about his dealings with women, allowing none in his household, even excluding his own sister and his nieces. He used to say that if they lived within the residence, other women would come to visit and to stay with them. It seems that St. Augustine enjoyed a bit of praise, and in fact that he felt obliged to combat this inclination. At the same time, his love for truth led him to welcome criticism of his writings. In his final years he carefully went through them and changed and deleted many parts. This evidence of his honesty and love of truth has visible proof in his two volumes summing up the changes, which are called The Retractations or The Retractions.

A Peerless Spiritual Guide: St. Augustine is a theologian’s theologian. His treatises are not for the average reader. Their fruit is better when prepared and selected by experts. But his Confessions, sermons and some letters can be used with much profit by all. What he says has great value for spiritual direction. St. Augustine’s complete dedication to God and his relentless logic in seeking God everywhere made him reach into the inner fibers of his being to express his thoughts and to lead others on a similar path. Following are a few random cull; How can you be proud unless you are empty? For if you were not empty (deflated), you could not be inflated. Our whole business, therefore, in this life is to restore to health the eye of the heart, whereby God may be seen. The love of truth requires a holy retiredness, and the necessity of charity a just employment.

Some people, in order to discover God, read books. But here is a great book: the very appearance of creating things. Look above you. Look below you. Note it; read it. God, whom you want to discover, never wrote that book with ink; instead, He set before your eyes the things that He had made. Can you ask for a louder voice than that? Why, heaven and earth shout at you: “God made me!” The whole life of a good Christian is a holy longing. What you long for, as yet you do not see; but longing makes you the room that shall be filled when that which you are to see shall come. When you would fill a purse, knowing how large a present it is to hold, you stretch wide its cloth or leather: knowing how much you are to put in it, and seeing that the purse is small, you extend it to make more room. So, by withholding the vision, God extends the; through longing, He makes the soul extend; by extending it, He makes room in it. So, Brethren, let us long, because we are to be filled.

When men here below throw lively parties to celebrate some occasion, they usually engage a band and have a choir of boys to sing in their houses. And when we hear snatches of it as we pass by, we say, “What’s going on here?” And we are told, “They are celebrating; it’s a birthday, or a wedding”; some reason to explain the festivities. In the house of God, the festivities go on forever—there are no merely passing occasions for celebrating there. It is an everlasting feast, with choirs of angels to sing on it; with God present in very person, there is joy unflagging, merriment unceasing. And it is from these eternal, everlasting festivities that the ears of our minds catch at something, a sweet melodious echo—but only if the world is not making a din.

The man who walks into this tent and turns over in his mind the wonderful things God has done for the redemption of the faithful is struck and bewitched by the sounds of that festival in Heaven, and drawn from them like the stag to the fountain of waters. (In Ps. 41). Sometimes there is a kind of contrariness apparent in the products of hatred and love: hatred may use fair words and love may sound harsh… Thus we may see hatred speaking softly and charity prosecuting; but neither soft speeches nor harsh reproofs are what you have to consider. Look for the spring. Search out the root from which they proceed. The fair words of the one are designed for deceiving, the prosecution of the other is aimed at reforming.

A Man of Contrasts: In the life of St. Augustine we have a dramatic summary of the contrasts in human life. We have a picture etched in strong colors of the depths and the heights possible in moral behavior. We realize again that a person can be many sided, and during one lifetime, he can, so to speak, be many persons. There is always an essential unity there, but if the spiritual and intellectual development had been stopped at any of various points along the way, the man would have been quite different.

In reviewing the life of St. Augustine, we gain an insight into the strength and the weakness of even the greatest of minds. Men have often quoted St. Augustine at cross purposes. We gain an insight into the difficulty of understanding any person completely. During his own lifetime and ever since, St. Augustine was and is a man intensely loved and hated. Of course, the same can be said of Christ. And we may wonder if this will not be true of anybody who follows Christ with all his heart. In our day, when we are so conscious of good public relations, we may wonder whether our relations with Christ may not come out second best.

A Giant in the Church: It is the common opinion that St. Augustine was, “with the possible exception of St. Thomas Aquinas, the greatest single intellect the Catholic Church has ever produced.” (Delaney, Dictionary of Saints). So great was St. Augustine’s influence that it dominated the Western world for a thousand years and has put its stamp on Catholic theology to this day.

St. Augustine’s theological depth and many sided ness have at times made him a hero to Protestant as well as to Catholic readers. Even where they disagree with him, they recognize his genius. In the complicated questions of grace and free will, St. Augustine’s authority has been claimed, though wrongly, by both Jansenists and Calvinists. This very aspect of his universal appeal springs from his effort to express the complete truth and from the fervor of his profound and complete dedication to God. St. Augustine’s greatness of spirit is brought out in the famous saying that has often been attributed to him: In necessaries Unitas, in Dubis Libertas, in omnibus Caritas—“In necessary things, unity; in doubtful things, liberty; in all things, charity.”

The most common picture of St. Augustine in art does not give a truly correct idea of him. For it shows St. Augustine comes upon a little boy at the seashore who is trying to pour the ocean into a small hole in the sand. Augustine tells the child that this is impossible—and is answered in gentle disapproval by the boy, who is really an angel, that it would be easier for him to put the ocean into the little hole than for Augustine to put the mystery of the Blessed Trinity into a small human mind. Versions of this picture have been done by the artists Murillo, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael and Dürer. The same legend has been applied to at least three other people besides St. Augustine, although the version featuring St. Augustine is by far the most famous. Though a good story, it is not quite fair to St. Augustine, because he knew full well that many Christian mysteries are incomprehensible.

It is this fact which helped to make him a mystic, for he sought illumination from God on these mysteries. He wrote his grand treatise, On the Trinity, over a period of 16 years (400–416) and meditated on this mystery daily. But at the same time, while seeking illumination from God and knowing the limits of the mind, he also knew that God had given man reason and that it is to be used to the fullest. He answered one critic who objected to his writings about the Trinity: “Perish the thought that our belief should be such as to prevent us from accepting or looking for reasons! We could not even believe, after all, unless we had reasonable souls.” St. Augustine’s appreciation of “the great light of reason” made him, probably the Church’s greatest philosopher and theologian, and he was the forerunner of the Scholastics of the Middle Ages. He is one of the four great Doctors of the Latin Church (the others being St. Ambrose, St. Jerome and St. Gregory the Great).

The truest picture of St. Augustine is that which shows him looking up toward Heaven, a pen in his left hand and a burning heart in his right. For he pursued the knowledge and love of God with mind and heart, with reason and with faith. He pursued truth, moreover, with an intellect guided and protected by the full support of a pure moral life. He speaks to us not only in flowing rhetoric, but heart to heart, as to another human being longing for that “Beauty ever ancient, ever new.” Bossuet calls St. Augustine the “Doctor of Doctors.” No higher praise can be spoken of his learning. But when all is said and done, we may wish to accept the judgment of his friend and biographer, Pisidius, who said that we can profit more from a knowledge of St. Augustine’s life than from a study of his writings. No higher praise of his holiness can be spoken. St. Augustine’s feast day is August 28.